breaking the spell of Breaking the Spell

I got all excited about philosopher Daniel Dennett's new book, Breaking the Spell, that brings scientific thinking and attitudes to bear on religion. (Yes, I am a nerd.)

I got all excited about philosopher Daniel Dennett's new book, Breaking the Spell, that brings scientific thinking and attitudes to bear on religion. (Yes, I am a nerd.) But reading H. Allen Orr's review of the book in the New Yorker deflated me. Dennett returns to the idea of memes, which I thought was the weakest aspect of his fascinating and convincing book on evolution, Darwin's Dangerous Idea. Apparently he wants to explain religion as a set of ideas that persist and spread—as living organisms survive and reproduce to pass on their genes—primarily because they are catchy, and the religions that last the longest and spread the widest are the catchiest, somewhat independent from whatever they do for the people who carry the ideas and beliefs around in their heads. (It reminds me of Tom Robbins' line in Another Roadside Attraction that animals are just a way for water to get from one place to another.)

Orr argues that unlike the concept of a gene in biology, the meme concept, 30 years on from its introduction in Richard Dawkins' The Selfish Gene, has yet to explain anything not explained before, predict anything interesting, or produce a testable scientific theory that would show that memes are indeed real actors underlying any bit of our cultural lives. "The existence of a God meme," Orr writes, "is no better established than the existence of God." So, he continues: "It's far from obvious that explainign unprovable beliefs with unprovable theories constitutes progress."

Then Orr attacks the whole point of Dennett's work in this area. Dennett says in the introduction that this is his first book aimed at a popular audience because he is concerned about religion's ill effects and wants to encourage debate and critical thinking. But it's hard to imagine that his book will have any impact on the larger world, though. As Orr wraps up his review:

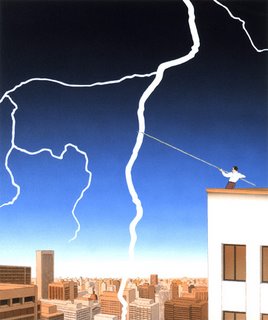

Religion is much more than a collection of transcendental and untestable assertions. It's also a potent social and political force, and, like any such force, it is sometimes prone to excess. The result is the usual roster of ills: intolerance, fanaticism, and, yes, terrorism. But it seems doubtful that solutions to these problems will emerge from anyone's laboratory.image by Guy Billout

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home