Monday, January 22

I'm retiring this blog and starting to post over on my new and improved, all-purpose website. Check it: masonmade.com. It's got my news articles for work, the continuation of this blog, plus random other voyeuristic stuff about my music tastes and pictures of bat faces.

Sunday, January 14

Downfall of civilizations

I'm thinking about the downfall of civilizations now, after having just watched "Downfall," the controversial movie about the end of Hitler's reign.

I'm thinking about the downfall of civilizations now, after having just watched "Downfall," the controversial movie about the end of Hitler's reign.One of the parts that got me thinking was when he's in his Fuhrerbunker, looking over the plans for a redevelopment of Berlin to make it into a center of culture and art that will last thousands of years. It's insane, because he acknowledges the city is getting destroyed, and says the destruction makes the plan easier, because clearing the rubble away would take less effort than demolishing the buildings.

But as in so many other moments in this movie, there's the glaring inconsistency that somehow the characters overlook, like the simultaneous destruction and the fervently believed-in plans for a city that will never be destroyed. Or some of them know this, but will never let on.

It made me think of the library at Alexandria, and how that, too, was supposed to be a place to store the world's knowledge for posterity, and it was all lost. Today, in the U.S., it probably feels to most Americans like there's no threat to most of the world's writing, art, and so on. But if two World Wars and everything else that happened in the past 100 years has any message, it's that we're not safe, even from those we consider on our side.

I don't mean to encourage some kind of paranoid siege mentality. I'm just thinking that if we want to do more to preserve cultural artifacts, we should be working on that now, rather than when things seem under threat.

People are scanning all sorts of things into computers—like I went to the Clay Math Institute in Cambridge on Friday and talked to them about how, among other things, they've scanned in the earliest existing copy of Euclid's Elements, the book that (as I understand it) is the beginning of geometry as we think of it today.

They have beautiful scans of the book taken with an ultra-high-resolution camera, but where are the images stored? How many servers hold them? Basically, for all our access to things online, how vulnerable are these things to getting wiped out? My guess is, pretty vulnerable.

Tuesday, January 9

Lilja 4-ever

I just watched Lukas Moodysson's movie "Lilja 4-ever"...

I just watched Lukas Moodysson's movie "Lilja 4-ever"...WARNING! PLOT SPOILER! PLOT SPOILER!

... about a young girl in one of the former Soviet republics who gets sold into prostitution in Sweden. When she finally escapes from her pimp at the end of the movie, I knew from the foreshadowing at the beginning that she was going to try to kill herself.

It would hopelessly depressing if she did it and, cut, that's the end of the movie, and I hoped that's not what would happen. I was pleased, sort of, when after she jumped from an overpass onto a freeway, the movie played on, with Lilya fooling around with her friend, who'd killed himself and who had come back before to look over her as a guardian angel. Now they both had wings and smiles.

That ending made me feel much better, and made the movie somehow more complete. I could feel that idea, that everything is going to be OK after you're dead, grabbing at my heart with little cloying claws—even though I don't believe at all in God, heaven, and the fairy tale kind of version of religion where you get to eat sundaes or play basketball or do whatever happy things you want to do forever and ever in heaven.

And I'm guessing Moodysson doesn't believe in all that either. So what was this ending all about?

Monday, January 8

Sunday, January 7

black hole by charles burns

I just read Charles Burns' huge graphic novel Black Hole literally in one sitting, except for getting a drink of water. I feel like my eyes are going to wither away now, and half the book made me feel like I was tripping along with the characters, but it blew me away.

His work might be familiar to you from the covers of The Believer. The story is, like many comics and graphic novels, all about the difficulties of adolescence.

But this one has a twist. There's a bug going between the kids at a school that turns them into freaks, with weird tumors, tails, mouths and other growths—the usual teenager awkwardness turned malignant. A bunch of them go out to live in the woods, but the strain of freakishness combined with teen angst is too much for one of them...

This was one of the most stunning pages in the book—especially after a bunch of creepy pages of decay that come before it. (Click image to see a larger version.)

His work might be familiar to you from the covers of The Believer. The story is, like many comics and graphic novels, all about the difficulties of adolescence.

But this one has a twist. There's a bug going between the kids at a school that turns them into freaks, with weird tumors, tails, mouths and other growths—the usual teenager awkwardness turned malignant. A bunch of them go out to live in the woods, but the strain of freakishness combined with teen angst is too much for one of them...

This was one of the most stunning pages in the book—especially after a bunch of creepy pages of decay that come before it. (Click image to see a larger version.)

writer's block insurance

I'm reading The Midnight Disease, largely about the neurobiology of writing and the various kinds of disorders related to writing, everything from extreme writer's block and aphasia (inability to understand words) to hypergraphia (written verbal diarrhea).

The author, who is a neurologist, had hypergraphia herself, and then after giving birth went through a depressive state with total writer's block. Let's hope my mercurial moods don't wind up giving me block. But in case they might, maybe I should get writer's insurance (see below for a New Yorker cartoon by Roz Chast; click pic to see bigger version). I also read in the New Yorker about Mongolian goat herders' insurance, so in case of drought or whatever and their herd falters, they're all set. If they can get that, why can't I get writer's insurance?

The author, who is a neurologist, had hypergraphia herself, and then after giving birth went through a depressive state with total writer's block. Let's hope my mercurial moods don't wind up giving me block. But in case they might, maybe I should get writer's insurance (see below for a New Yorker cartoon by Roz Chast; click pic to see bigger version). I also read in the New Yorker about Mongolian goat herders' insurance, so in case of drought or whatever and their herd falters, they're all set. If they can get that, why can't I get writer's insurance?

Saturday, January 6

Thursday, January 4

Coal mining causing earthquakes

Australia's biggest earthquake ever, along with about 200 other earthquakes worldwide, have been caused by coal mining, a new study says.

Australia's biggest earthquake ever, along with about 200 other earthquakes worldwide, have been caused by coal mining, a new study says.I'm surprised that our mines could have this big of an effect.

Read more about it on National Geographic News.

Monday, January 1

giant squid captured!

The elusive giant squid has finally been captured alive—although it didn't live long.

If you thought the giant squid caught on film a few months back was pissed (see how he took Us Weekly to task in his article in McSweeney's), I bet this one would have gone ballistic if he hadn't died.

bat gives Gene Simmons tongue envy

This is one of my favorite juxtapositions ever. Read more about this bat, which has the biggest tongue in the world (relative to its body size), on National Geographic News.

Thursday, November 30

how to calculate pi by throwing frozen hotdogs

WikiHow had this funny version of a classic experiment for generating an approximation of pi, the number (3.1417...) that's you get when you divide a circle's circumference by its diameter. But why do that when you can throw hotdogs?

WikiHow had this funny version of a classic experiment for generating an approximation of pi, the number (3.1417...) that's you get when you divide a circle's circumference by its diameter. But why do that when you can throw hotdogs?All it takes is some kind of long, slender, rigid thing you can throw around. (For all you with potty-minds, that last part is key. You have to be able to throw it.) And then you need some tape or something to mark out a set of lines on the floor. Then you fling your thing (hotdog, whatever) over and over and count how many times the hotdog crosses the lines, or doesn't. Then you do a shockingly simple calculation and, voila, pi!

Link to Wikihow for more details.

Wednesday, November 8

the trouble with singing sand

Sand can sing loud, sending out booms or squeaks when it slides down the side of a dune—but no one is sure why. I wrote about this in July for Seed, reporting on the latest findings about the singing sand.

Sand can sing loud, sending out booms or squeaks when it slides down the side of a dune—but no one is sure why. I wrote about this in July for Seed, reporting on the latest findings about the singing sand.But it was somewhat disappointing because of all the experts I talked to who are working on this problem—and, not surprisingly, there are only a few—it seemed none of them could agree on much of anything to do with how the sand is making this sound.

I thought, how complicated can this be? We can see stars billions of light years away, and probe inside atomic nuclei, but can't figure out why this sand squeaks?

Partly, I'm sure, it's because not many people have worked on it. And partly because it's a trickier problem than it seems at first. But part of it, too, seems to be sociology.

Though you might think singing sand is a fun, maybe somewhat frivolous project for scientists to work on, the various people who work on singing sand have bitter disagreements about their findings. Physics Web reports on this in their latest issue, and it's a fascinating story of science in action.

Also, I just finished reading Lee Smolin's book The Trouble with Physics, which is really about the trouble with fundamental physics, especially string theory. This theory is aiming to undercover the very most basic laws of nature, and bring together the fundamental theories that we have now—quantum physics and Einstein's relativity theories—under one umbrella.

Also, I just finished reading Lee Smolin's book The Trouble with Physics, which is really about the trouble with fundamental physics, especially string theory. This theory is aiming to undercover the very most basic laws of nature, and bring together the fundamental theories that we have now—quantum physics and Einstein's relativity theories—under one umbrella.But too many string theorists have bought too much into their own program, Smolin argues, so that it's not clear if the whole area of string theory will ever be fruitful or testable. That is, it's still not clear whether it has anything at all to do with reality.

It seems here it's the flip side of the situation with the singing sand dunes. There are a whole bunch of physicists working on string theory, devoting their lives to it, rather than just a few, independent researchers working on singing dunes as a side project. In string theory, it requires a lot of faith and optimism—I've heard this from people who work in the field—because there's no physical evidence yet that they're on the right track. With the singing dunes, there's clearly something happening, but it's not clear how it happens.

So even if there's too much faith and agreement within the string theory community, it's nice to see physicists still bickering over something like singing dunes. That's how some of the best science gets done. Maybe the trouble with physics is not enough trouble between physicists.

Thursday, October 26

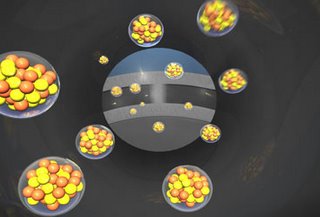

Newly Discovered Element 118 Helps Chart the Seas of Instability

Here's my latest article, on Seed's Web site:

Here's my latest article, on Seed's Web site:Based on the briefest of glimpses, scientists are mapping out a shadowy "island of stability," a harbor of hope within a vast and deadly "sea of instability." These modern-day Magellans are nuclear physicists, and by colliding atoms at high speeds, they are creating the heaviest elements ever seen with the hope that they will find this island: the few precious isotopes that do not decay instantaneously.

Now they've discovered the largest element yet, number 118: In a paper published recently in the journal Physical Review C, a collaboration of Russian and American researchers presents evidence for the as-yet-unnamed element. They say they observed 118 three times over a three-year search.

Atoms have dense nuclei that are composed of neutrons and positively-charged protons. The higher an element is on the periodic table, the more protons and neutrons—and therefore the more mass—a nucleus in one of its atoms has.

Creating superheavy nuclei is a delicate balancing act. Within the nucleus, two forces fight for control. The protons' electric charges make them repel each other fiercely. But the strong nuclear force, which binds protons and neutrons alike, pulls them together. For each element, there are only a few combinations of protons and neutrons—each of which is called an isotope—that will stick together long enough to count as an actual atom.

"At some point, the forces that are holding the nucleus together are not going to let another proton be shoved in there," said Nancy Stoyer, co-author of the study and a scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. "You put [another proton] in there and it's going to immediately break apart. At some point, we're going to reach the end of the elements. Where that is, we don't know."

Read more

Monday, October 16

Mobile Games Superimpose Virtual Fun on the Real World

Here's my latest article, on National Geographic News, part of a series they'll be posting on "digital places":

A man calling himself Long John Silver sits in a New York City cafe, unsheathes his laptop, and checks the prices of spices at his location, known to him as Treasure Island.

A man calling himself Long John Silver sits in a New York City cafe, unsheathes his laptop, and checks the prices of spices at his location, known to him as Treasure Island.

During a break at the office, Silver wins a fierce battle against Blackbeard, who works downstairs on the fifth floor, and captures a load of gems.

This isn't someone's delusional world, but rather a hypothetical round of a new game called Plundr.

The swashbuckling adventure made its debut at the Come Out and Play street games festival held in New York City from September 22 to 24.

"Everyone loves pirates," said Kevin Slavin, co-founder of area/code, the company that created Plundr (related news: "Grim Life Cursed Real Pirates of Caribbean" [July 11, 2003]).

So the company took piratical inspiration for their latest game, which superimposes a world of raiding and trading on our everyday environment.

In Plundr, players move within a city as their computers track their movements. They trade goods or build up their arsenals to prepare for battles with other "pirates" cruising the city streets.

The roving role-playing game is an example of what have been dubbed mobile social games—games that use global positioning systems (GPS) and other location-based technologies to track players' movements within a fictional world layered on top of the real world.

Play Driving Demand

A variety of mobile social games have been developed for cell phones or personal digital assistants (PDAs), although only a handful so far have achieved wide popularity.

"This is really a nascent field, especially in the [United] States," Slavin said.

Read more...

Photograph by Aaron Straup Cope

A man calling himself Long John Silver sits in a New York City cafe, unsheathes his laptop, and checks the prices of spices at his location, known to him as Treasure Island.

A man calling himself Long John Silver sits in a New York City cafe, unsheathes his laptop, and checks the prices of spices at his location, known to him as Treasure Island.During a break at the office, Silver wins a fierce battle against Blackbeard, who works downstairs on the fifth floor, and captures a load of gems.

This isn't someone's delusional world, but rather a hypothetical round of a new game called Plundr.

The swashbuckling adventure made its debut at the Come Out and Play street games festival held in New York City from September 22 to 24.

"Everyone loves pirates," said Kevin Slavin, co-founder of area/code, the company that created Plundr (related news: "Grim Life Cursed Real Pirates of Caribbean" [July 11, 2003]).

So the company took piratical inspiration for their latest game, which superimposes a world of raiding and trading on our everyday environment.

In Plundr, players move within a city as their computers track their movements. They trade goods or build up their arsenals to prepare for battles with other "pirates" cruising the city streets.

The roving role-playing game is an example of what have been dubbed mobile social games—games that use global positioning systems (GPS) and other location-based technologies to track players' movements within a fictional world layered on top of the real world.

Play Driving Demand

A variety of mobile social games have been developed for cell phones or personal digital assistants (PDAs), although only a handful so far have achieved wide popularity.

"This is really a nascent field, especially in the [United] States," Slavin said.

Read more...

Photograph by Aaron Straup Cope

US & Iran argue over who actually talks to God

Bush says he's inspired by God, he was chosen by God to be president, blah blah blah.

Iran's president is saying the same about himself—and that Bush is actually inspired by Satan:

Link to the BBC article on Ahmadinejad's inspirations.

Iran's president is saying the same about himself—and that Bush is actually inspired by Satan:

According to the Iranian media, Mr Ahmadinejad said he had inspirational links to God, and went on to say that if you were a true believer, God would show you miracles.It would be so much easier if at least a few other people could talk to God or Satan to confirm or deny these claims.

Then the Iranian president said Mr Bush was similar to him.

According to Mr Ahmadinejad, the US president also receives inspiration - but it is from Satan.

He repeated: "Satan inspires Mr Bush."

Link to the BBC article on Ahmadinejad's inspirations.

Thursday, October 12

sometimes they play so strangely

I went to see Matmos tonight at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. I interviewed them a few months back for an interview in Seed Magazine, and they showed me their equipment when I visited their apartment. I'd never seen them live, though, so it was cool to see how they put together all the strange noises—from squeaking rods, crackling tin foil, and squeaking metal rods—into songs, of sorts.

I went to see Matmos tonight at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. I interviewed them a few months back for an interview in Seed Magazine, and they showed me their equipment when I visited their apartment. I'd never seen them live, though, so it was cool to see how they put together all the strange noises—from squeaking rods, crackling tin foil, and squeaking metal rods—into songs, of sorts.Their first few songs were with a group called So Percussion who did fabulous xylophone backing for the most melodious of their songs, "Y.T.T.E." (link to sample of the song on emusic), which descended into chaos, with M.C. Schmidt banging on the wires inside his piano and everyone going crazy (except Drew Daniels on the laptop, who was still staidly clicking away—it's kinda hard to freak out on a laptop). Then they toned down the noise and went back into another melodious piece, (I think) "For the Trees", off their album "The Civil War."

They did a song where Schmidt read the text of a speech by Venesuelan president Hugo Chavez at the UN recently, where he called Bush the devil. (Link to a CNN article with links to video of Chavez's speech.)

They played a movie they made of a man's hand slapping another man's butt, and they tweaked the sound of the slap so it sounded tinny and artificial, and then back to realistic, except that it sounded like increasingly harsh slaps. It was hard not to wince at the slaps, and people laughed out loud, even though you could see on the video that it was just the same clip being looped. (An older couple got up and left halfway through this video, apparently offended—the only people to get up during the whole show.)

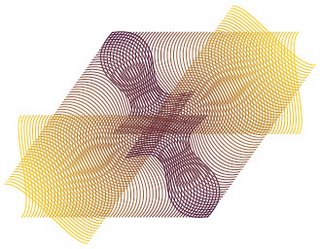

They put the clip into each of four quadrants on the screen and played with the timing of the slaps so weird rhythms came out of it, just like in Steve Reich's music, which So Percussion played in the opening of the show. Reich's songs play with simple, repeated loops that often ride on the edge of being annoying, except every so often he switches the rhythm of them in a subtle way that gives rise to new, emergent patterns, like how simple sets of lines can create the Moire effect (click here for a cool demo of it).

They put the clip into each of four quadrants on the screen and played with the timing of the slaps so weird rhythms came out of it, just like in Steve Reich's music, which So Percussion played in the opening of the show. Reich's songs play with simple, repeated loops that often ride on the edge of being annoying, except every so often he switches the rhythm of them in a subtle way that gives rise to new, emergent patterns, like how simple sets of lines can create the Moire effect (click here for a cool demo of it).It reminded me of a radio show I heard recently, where listening to loops of speech can make the talking seemingly transform into singing. The radio show producers did an awesome job of mixing up a linguist's story of how she found this effect, with the actual recording so you can experience the effect yourself, with a loop of the phrase "sometimes behave so strangely." The show is kinda long, but the key part is from around 1:30 to 3:30 into the show. Listen to it on WNYC's website.

Wednesday, October 11

FBI Agents Still Lacking Arabic Skills

This Washington Post article lays out a disturbing lack of skill in U.S. security—and not just because it hurts their ability to catch the "bad guys," but also because it means they might not have a very good idea of what's going on in Arabic-speaking communities:

The situation makes it so that simply using a foreign language is like having an unbreakable code:

Five years after Arab terrorists attacked the United States, only 33 FBI agents have even a limited proficiency in Arabic, and none of them work in the sections of the bureau that coordinate investigations of international terrorism, according to new FBI statistics.Can't they just send agents to school to learn these languages?

The numbers reflect the FBI's continued struggle to attract employees who speak Arabic, Urdu, Farsi and other languages of the Middle East and South Asia...

The situation makes it so that simply using a foreign language is like having an unbreakable code:

A study released last week, for example, found that three terrorists housed at a federal prison in Colorado were able to send more than 90 letters to fellow extremists overseas, in part because the prison did not have enough qualified language translators to understand what was happening.But since we're in for a long, long war, apparently the government thinks this language issue can wait until the next generation of FBI agents grows up:

The Bush administration early this year unveiled a "National Security Language Initiative" aimed at encouraging more instruction in "critical" languages in elementary schools, secondary schools and universities.

Friday, October 6

2006 Ig Nobels Award Research in Hiccups, Poop, and Bad Writing

Here's my latest story, on National Geographic News:

The finicky eating habits of dung beetles, the attraction of mosquitoes to Limburger cheese, and "digital rectal massage" as a cure for hiccups—these were among the findings that garnered researchers Ig Nobel awards yesterday.

The finicky eating habits of dung beetles, the attraction of mosquitoes to Limburger cheese, and "digital rectal massage" as a cure for hiccups—these were among the findings that garnered researchers Ig Nobel awards yesterday.

On the heels of the original Nobel prizes announced this week, the Ig Nobels held their 16th annual award ceremony at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The winners all made discoveries that "make you laugh and then make you think," said Marc Abrahams, who started the Ig Nobels.

The awards were inspired by his work as editor of the Annals of Improbable Research, which publishes reports of odd findings that appeared first in reputable science journals as bona fide discoveries.

Hiccup Cure?

On a stage strewn with paper airplanes flung by the audience, the Ig Nobel winners received their awards.

A crowd favorite was the Medicine award, which went to doctors who probed the edges of medical practice to find a cure for incessant hiccups.

They found that as a last resort an effective remedy is a "digital rectal massage."

The first to use this technique was Francis Fesmire, a doctor at Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

He treated a patient in the emergency room who suffered from hiccups every two seconds for three days.

"Initially gagging and tongue-pulling maneuvers were attempted with no change," Fesmire reported in the Annals of Emergency Medicine.

After various other attempts, Fesmire resorted to sticking his finger where the sun don't shine. Applying a slow circular motion stopped the hiccups within seconds.

"I want to make it clear, I've done this once to a patient," Fesmire said. "It worked, and I was pleased. I have no desire to do it again."

Fesmire, who walked out to receive his award with his curative digit held up high, shared the prize with a team of Israeli doctors who later put their fingers on the same cure.

Read more on the National Geographic News site.

The finicky eating habits of dung beetles, the attraction of mosquitoes to Limburger cheese, and "digital rectal massage" as a cure for hiccups—these were among the findings that garnered researchers Ig Nobel awards yesterday.

The finicky eating habits of dung beetles, the attraction of mosquitoes to Limburger cheese, and "digital rectal massage" as a cure for hiccups—these were among the findings that garnered researchers Ig Nobel awards yesterday.On the heels of the original Nobel prizes announced this week, the Ig Nobels held their 16th annual award ceremony at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The winners all made discoveries that "make you laugh and then make you think," said Marc Abrahams, who started the Ig Nobels.

The awards were inspired by his work as editor of the Annals of Improbable Research, which publishes reports of odd findings that appeared first in reputable science journals as bona fide discoveries.

Hiccup Cure?

On a stage strewn with paper airplanes flung by the audience, the Ig Nobel winners received their awards.

A crowd favorite was the Medicine award, which went to doctors who probed the edges of medical practice to find a cure for incessant hiccups.

They found that as a last resort an effective remedy is a "digital rectal massage."

The first to use this technique was Francis Fesmire, a doctor at Erlanger Hospital in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

He treated a patient in the emergency room who suffered from hiccups every two seconds for three days.

"Initially gagging and tongue-pulling maneuvers were attempted with no change," Fesmire reported in the Annals of Emergency Medicine.

After various other attempts, Fesmire resorted to sticking his finger where the sun don't shine. Applying a slow circular motion stopped the hiccups within seconds.

"I want to make it clear, I've done this once to a patient," Fesmire said. "It worked, and I was pleased. I have no desire to do it again."

Fesmire, who walked out to receive his award with his curative digit held up high, shared the prize with a team of Israeli doctors who later put their fingers on the same cure.

Read more on the National Geographic News site.

Wednesday, October 4

Fox transformed disgraced Republican into Democrat

This is unbelievable! Fox News identified disgraced Republican congressman Robert Foley as a Democrat on several occasions. They even had the caption "Did Dems ignore Foley emails to preserve seat?"

See the screen shots on Boing Boing.

In another news story on the scandal, Representative Ray LaHood (R-IL—yes, really a Republican), said that the houses of government aren't safe for the young.

All that said, I think that there are far worse things going on in our government than the Foley thing, yet people don't get too worked up over it.

See the screen shots on Boing Boing.

In another news story on the scandal, Representative Ray LaHood (R-IL—yes, really a Republican), said that the houses of government aren't safe for the young.

It's not the speaker who should go, LaHood said, but the "antiquated" page system that brings 15- and 16-year-olds to the Capitol and has resulted in scandals in the past.So apparently our representatives simply can't help themselves, and aren't safe for young adults, let alone young children, to be around. So much for family values.

"Some members betray their trust by taking advantage of them. We should not subject young men and women to this kind of activity, this kind of vulnerability," LaHood said in a CNN interview.

All that said, I think that there are far worse things going on in our government than the Foley thing, yet people don't get too worked up over it.

Thursday, September 28

"Resurrecting" Bacteria's Secret Revealed

Here's my latest article, on National Geographic News:

Death is the ultimate fate for most bacteria blasted by huge doses of radiation or parched by a severe lack of water. The genetic material irreversibly splinters into hundreds of pieces, dooming the organisms as surely as Humpty Dumpty.

Death is the ultimate fate for most bacteria blasted by huge doses of radiation or parched by a severe lack of water. The genetic material irreversibly splinters into hundreds of pieces, dooming the organisms as surely as Humpty Dumpty.

But a few bacteria can "resurrect" themselves by quickly piecing their DNA back together—a strange ability that has mystified biologists for decades.

Now researchers have figured out how one species of these phoenix-like bacteria can rise from the ashes.

A group led by Miroslav Radman, a molecular geneticist at Université René Descartes in Paris, France, announces its findings today on the Web site of the journal Nature.

Radman's group studied a bacteria called Deinococcus radiodurans, which survives in sunbaked deserts and rock surfaces. (Related: "'Miracle' Microbes Thrive at Earth's Extremes" [September 2004].)

The organism can withstand massive doses of radiation and can even survive being completely dried out.

When that occurs, "there is no metabolism," Radman said. "The genome is shattered into hundreds of pieces. It is a dead cell.

"But out of this horrendous damage, it can resurrect."

Keeping It Together

DNA normally acts like a blueprint, telling cells how to cook up the proteins that make life possible (get a genetics overview).

But shredding these instructions renders them useless. Once DNA is split into multiple pieces, there's usually no way a cell's internal machinery can figure out how to piece everything back together again.

Reconstruction must be precise, because a message restitched in the wrong order is gibberish, dooming the organism.

Unlike most bacteria, however, D. radiodurans contains multiple copies of its genetic material, which can act as backups for each other, Radman says.

Imagine that a cell's DNA holds the message "Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall."

Since the spots where DNA breaks because of radiation or damage are random, each copy of the genetic material will likely have breaks in unique locations.

So if one DNA strand breaks into the split messages "Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall" and "Humpty Dumpty had a great fall," there's likely another chunk of material floating around that can bridge the gap.

The material might read "sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty," for example.

The bacteria then chemically glue matching pieces together. Once they're bound, the cells fill in the missing parts of each of the two stuck-together copies, the study shows.

Using such clues, D. radiodurans can piece together all of its DNA in about three hours, even if it was split into hundreds of pieces.

"It's true that DNA is life," Radman said.

"As long as you can reconstitute the database of life, which is DNA, you can ... start life again."

"Miracle" Organism?

The new study "is certainly the biggest advance in understanding the mechanism of radiation resistance" in this well-studied species, said John Battista, a biology professor at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan.

Other radiation-resistant microorganisms might use the same mechanism, Battista and Radman agree.

The process could also inspire ideas for repairing our own cells, Radman says.

"It could teach us, maybe one day, how to resurrect dead or close-to-dead neurons [brain cells]," Radman said.

"I joke in the lab that we're going to get a grant from the Vatican titled 'The Molecular Basis of Resurrection.'"

Death is the ultimate fate for most bacteria blasted by huge doses of radiation or parched by a severe lack of water. The genetic material irreversibly splinters into hundreds of pieces, dooming the organisms as surely as Humpty Dumpty.

Death is the ultimate fate for most bacteria blasted by huge doses of radiation or parched by a severe lack of water. The genetic material irreversibly splinters into hundreds of pieces, dooming the organisms as surely as Humpty Dumpty.But a few bacteria can "resurrect" themselves by quickly piecing their DNA back together—a strange ability that has mystified biologists for decades.

Now researchers have figured out how one species of these phoenix-like bacteria can rise from the ashes.

A group led by Miroslav Radman, a molecular geneticist at Université René Descartes in Paris, France, announces its findings today on the Web site of the journal Nature.

Radman's group studied a bacteria called Deinococcus radiodurans, which survives in sunbaked deserts and rock surfaces. (Related: "'Miracle' Microbes Thrive at Earth's Extremes" [September 2004].)

The organism can withstand massive doses of radiation and can even survive being completely dried out.

When that occurs, "there is no metabolism," Radman said. "The genome is shattered into hundreds of pieces. It is a dead cell.

"But out of this horrendous damage, it can resurrect."

Keeping It Together

DNA normally acts like a blueprint, telling cells how to cook up the proteins that make life possible (get a genetics overview).

But shredding these instructions renders them useless. Once DNA is split into multiple pieces, there's usually no way a cell's internal machinery can figure out how to piece everything back together again.

Reconstruction must be precise, because a message restitched in the wrong order is gibberish, dooming the organism.

Unlike most bacteria, however, D. radiodurans contains multiple copies of its genetic material, which can act as backups for each other, Radman says.

Imagine that a cell's DNA holds the message "Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall."

Since the spots where DNA breaks because of radiation or damage are random, each copy of the genetic material will likely have breaks in unique locations.

So if one DNA strand breaks into the split messages "Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall" and "Humpty Dumpty had a great fall," there's likely another chunk of material floating around that can bridge the gap.

The material might read "sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty," for example.

The bacteria then chemically glue matching pieces together. Once they're bound, the cells fill in the missing parts of each of the two stuck-together copies, the study shows.

Using such clues, D. radiodurans can piece together all of its DNA in about three hours, even if it was split into hundreds of pieces.

"It's true that DNA is life," Radman said.

"As long as you can reconstitute the database of life, which is DNA, you can ... start life again."

"Miracle" Organism?

The new study "is certainly the biggest advance in understanding the mechanism of radiation resistance" in this well-studied species, said John Battista, a biology professor at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan.

Other radiation-resistant microorganisms might use the same mechanism, Battista and Radman agree.

The process could also inspire ideas for repairing our own cells, Radman says.

"It could teach us, maybe one day, how to resurrect dead or close-to-dead neurons [brain cells]," Radman said.

"I joke in the lab that we're going to get a grant from the Vatican titled 'The Molecular Basis of Resurrection.'"